Dust, it is said, is made primarily of shed human skin. But is the dust in my house only my dead skin? Or has someone else’s skin come in?

Image by Austin Ban via Unsplash.com

Dust, it is said, is made primarily of shed human skin. But is the dust in my house only my dead skin? Or has someone else’s skin come in?

Image by Austin Ban via Unsplash.com

ropey clouds at sunset

played out over a beryl sky

the tide slipping out

![]()

in a quiet room

only the sound of pages turning

pen scratching paper

![]()

asleep in the cabin

the restless heart of the sea

echoes in her chest

Image by Robin Anderson

“Pa! They’re here.”

“Who?”

“The crows.”

“Jeez, Ma, give it a rest.”

“They’re watching.”

“What?”

“The garden. They’re watching, just waiting for the plants to grow. To ripen.”

“Ma!”

“Then they’ll do their dirty work.”

“Yer crazy, cut it out!”

“Pa! One landed!”

“Wait, Ma, no! Come back. Ah shoot! Crow for dinner again.”

She rode into town on a mean tide. Exhausted and dirty, she figured she was washed up, done for. But in the morning she changed her mind, cleaned up and put on the paint that made her feel young again. At an open air market she picked up a fellow and decided to go back to the old ways, the siren song, maybe lure him to his death?

No luck. Instead he placed her on a shelf with glass floats and a wooden fish.

Now she dreams of the sea.

Image by Robin Anderson

craving solitude

I search a pink wilderness

the shopping mall

![]()

thrum of water pump

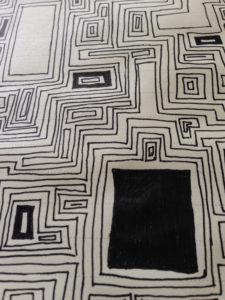

my neighbor’s carpets are clean

Stanley steams again

![]()

day closes in now

air redolent of evening

Hamburger Helper™

Image from Flikr/commons

![]()

dip, dart, twist, soar, slide

above wind tossed branches

ecstatic crow flies

by Harrison Fulop

First of Summer. Now darkness grows.

Image by Robin Anderson

e noticed her first. Tall and beautiful, she gazed about the garden until, at last, she saw him. She looked away quickly, confused. Was it usual to be stared at so rudely? She fled into the shadows.

e noticed her first. Tall and beautiful, she gazed about the garden until, at last, she saw him. She looked away quickly, confused. Was it usual to be stared at so rudely? She fled into the shadows.

But she returned. She grew used to seeing him, watching her. He did nothing to alarm her. One day, to both their surprise, she smiled.

They talked all summer, about their hopes, fears, eventually about their future together. But in their swift slide into love, they forgot one thing.

*****

“Honey, it’s time to bring the garden decorations in. It’s going to freeze tonight.”

When I read her stories, as I do, at times obsessively, I become uncomfortable with the way she seems mired in her awareness of her own consciousness, her self-conscious awareness of herself and I wonder, uncomfortably, if I am mired in her self-consciousness or if she is mired in my awareness of my consciousness, my self-conscious awareness of how I am obsessively mired in her stories.

When I read her stories, as I do, at times obsessively, I become uncomfortable with the way she seems mired in her awareness of her own consciousness, her self-conscious awareness of herself and I wonder, uncomfortably, if I am mired in her self-consciousness or if she is mired in my awareness of my consciousness, my self-conscious awareness of how I am obsessively mired in her stories.

Image by Harrison Fulop

Heat and dust. The little girl kicked a stone down the road. No fair! Sent to the store twice in one day, a quarter clutched in her small, sweaty hand.

At the corner the old woman with the sun hat still worked in her yard. This morning she’d been clipping roses, now she was cutting rhubarb with a sharp knife. Whack! at the ground. Whack! again at the top. A pile of shiny red stalks at her feet, huge wilting leaves heaped on the grass.

Little Girl put her head down and walked faster. Too late. “Barbara Jayne! Would you like to take some rhubarb to your mother?” “No! I hafta go to the store!” She broke into a run. “Your mother makes such lovely pies.”

Little Girl ran faster down the long hill. She stopped at the crossing, hopped into the street as a car horn blared, raced to the curb and up the steps to the store. Inside it was stuffy but cooler. The fat storeman smoked at the back counter, looked up from his newspaper. “Back again, huh?” Little Girl laid the quarter on the counter. “Loaf of bread, quart of milk.” The storeman’s eyebrow shot up. “Please!”

He fetched the milk from the icebox, the bread from the bin, took the quarter. “You got change comin’ or do you want some candy?” “No!” Little Girl grabbed the groceries. “Ma says put it on her account.” She slammed out the door, into the blinding afternoon.

The hill was steeper now that she was walking up it. She was thirsty, should have bought a soda. But Sister would have seen the bottle and told on her. Pooh. She stopped, tried to put the loaf of bread on her head for shade. It wouldn’t stay, dropped in the dusty road. A car was coming! She picked up the loaf, wiped the package clean on her dress and turned her back on the swirl of dust stirred up by the passing auto.

By the time she reached the top of the hill, Little Girl thought a drink of milk might be a good idea. Nope. She’d be in trouble with Sister for opening the bottle.

At the corner, Old Woman had disappeared from her yard, the rhubarb stalks were gone, too. But the big green leaves still lay on the grass. Little Girl looked up and down the road. She looked at Old Woman’s house. No one. Setting the milk and bread at the side of the road, she picked up a rhubarb leaf, plonked it on her head. Cool relief!

Little Girl walked toward home, remembering, in the nick of time, to turn back and fetch the bread and milk from the roadside.

“Hurry up, slow poke! That milk will be curdled by the time you get in here.” Sister stood on the porch. “What do you have on your head?” Ma stood at the kitchen window, laughing.

“Sun hat!” Little Girl tipped her head back, stuck out her tongue.

Sister bounded off the porch, jerked the milk and bread out of Little Girl’s hands. “Come on! Ma’s gonna make a rhubarb pie for dinner. You gotta go to the store for butter.”